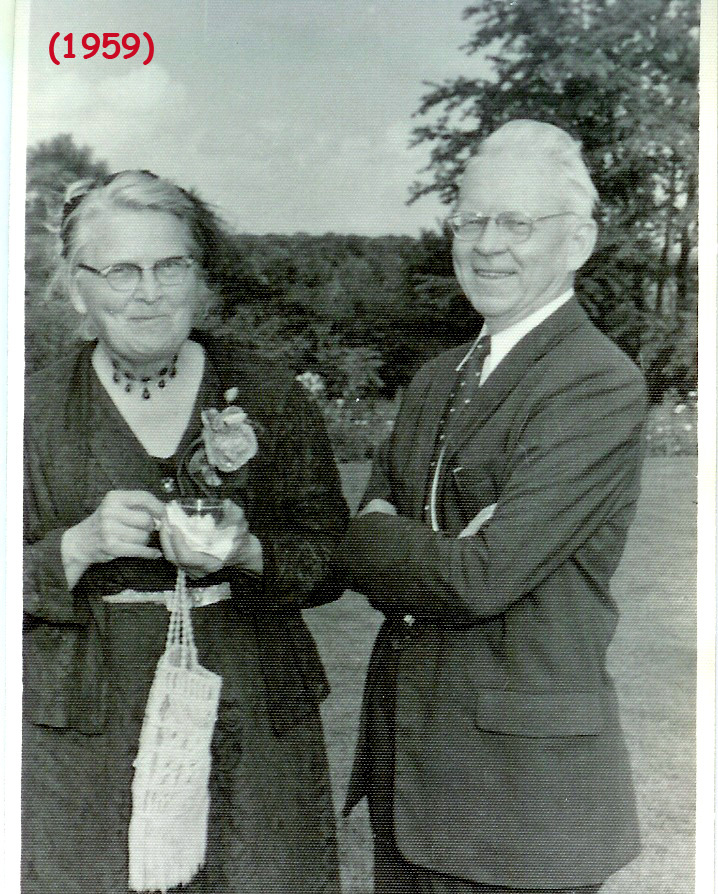

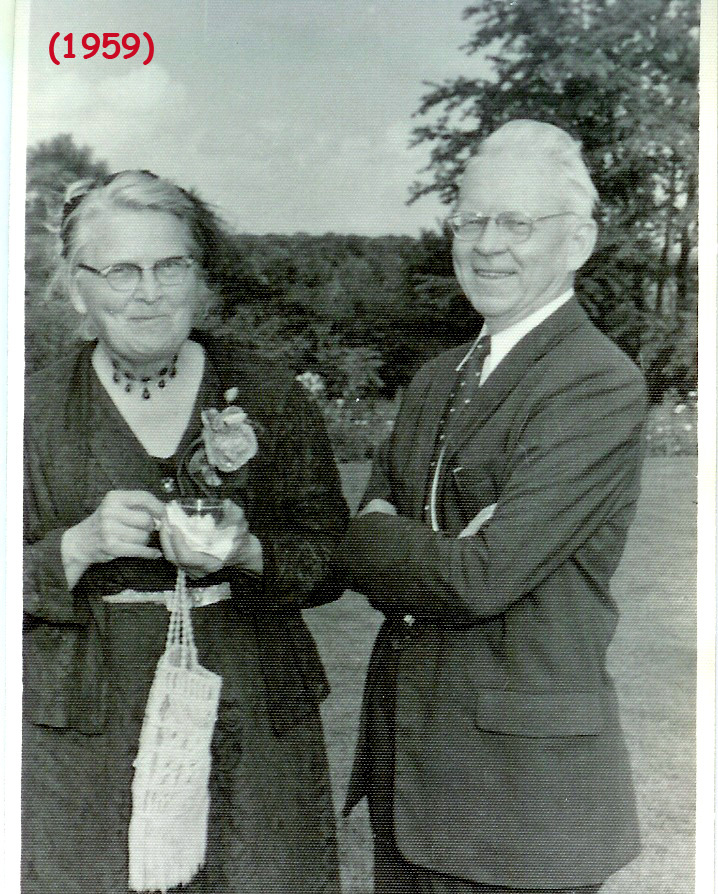

PAUL

AND HARRIET (FISCHER) NILSON

approximate

dates and places of their years in Turkey with ABCFM

1911—Paul

graduates from Beloit College. Begins

short term in Tarsus, Turkey

1912—Harriet Fischer graduates from Wheaton College. Teaches one year in California.

1913—Harriet

goes to Adana Turkey to begin short term in the girls’ school.

1915—Harriet

and Paul are engaged. Paul finishes

his term in Tarsus, returns to study in Hartford Theological Seminary.

1917—Harriet’s

term is finished, also war conditions force Americans to leaveTurkey

1918—Paul

graduates from Hartford. Paul and

Harriet married in June.

1919—March.

Faith Elizabeth is born. The

family returns to Tarsus.

1920

to 1924—Paul becomes head of Tarsus. Organizes

relief activities, as Turkish War for Independence begins causing food shortages

etc. in Tarsus. Baby Faith dies.

Three more babies are born and die. Doctors

insist on a transfer to a healthier climate.

1925—1926.

Paul studies for graduate degree in education at Universisty of Chicago.

One baby born, one conceived during this interval.

1927—Paul

returns to Kayseri/Talas station in Turkey (higher, drier climate)

Some general mission work, Mostly work on reopening the school in Talas.

There had been both a boys’ school and a girls’ school, as well as a

hospital in Talas. Harriet

returns with a toddler and an infant, May and Paul Jr.

(Paul Senior is Paul Emmanuel, Paul Jr. is Paul Herman)

1928

_1952 ABCFM

reopens the Talas boy’ school. Nilsons continue there until the fall of

1952. Sylvia is born Sept. 1928,

Dorothy is born June 1930.

1934-1935—the

whole family on furlough in America. Technically

a mission couple is supposed to have a furlough every seven years.

During war conditions it didn’t always work that way.

1943-44—Harriet

brings the four children back to America for school.

School shorthanded, Paul can’t leave.

1946-47—Paul

finally gets a furlough with Harriet in charge of the school.

1950-51

Both are on furlough together. Much

travel to speak in churches, etc.

1951-52—the

last year in Talas.

1952-57--

General mission work among the many ancient Christian groups in that far

eastern section of Turkey.

1957-1961

– Retirement from the Mission board. They

get an invitation to teach in a private Turkish school, specializing in English.

(To supplement the over-crowded public schools, businessmen in many towns

in Turkey opened private schools where they tried to get British or American

teachers to teach. English was now

the favored international language.)

1961-1964—Paul

and Harriet, plus Jim and Dorothy (Nilson) Fyfe teach in the private school in

Iskenderun, Turkey.

1965

Paul and Harriet settle in Wheaton for their declining years.

D.F.

Nov. 2005

Some

introductory information: Paul

E. Nilson’s father had come to

Harriet

Fischer came from a family of educators. Her

father, a second generation German, taught

German and astronomy at

I

am sending some selections from the

book I wrote about my parents for my relatives.

The sources for the book include my parents’ letters and reports, the

first edition of Dr. Frank Stone’s Academies

for Anatolia, Allen Bartholomew’s A

History of Tarsus American School, Justin

McCarthy’s Ottoman Peoples, End of Empire, and

Halide Edip Adivar’s memoir, House

with Wisteria.

In

the first part of these selections I use the Nilson’s names, Paul and Harriet.

In the Talas section I use ‘my mother,’ and ‘my father.’

since I was a child during those years.

I hope this change of names is not confusing.

The

paragraph about education in the

My

computer does not have the Turkish letter markings.

When I copy directly from the old letters, I use the old spellings.

Sometimes I use ‘sh’ because

I don’t have cedilla. I hope you

can fill in the correct markings.

SELECTIONS

FROM STORIES FROM THE VINEYARD

by

Dorothy Nilson Fyfe

There

were a number of minority populations in the

In the late 1800s, early 1900s there was an effort to make some reforms.

It was possible for a woman like Halide Edip Adivar to rise to public

prominence, both as a writer and as an educator. According

to her memoir, House with

Wisteria, her education was a

combination of a school centered in

the mosque, private tutoring, and

education in one of the American girls’ schools in

In

1911

Harriet

Fischer graduated from

During

the school year, teachers, doctors and nurses from

As

Paul’s term in

1915

THROUGH 1919

It was a difficult time for the newly engaged couple,

living in the shadow of war that engulfed Europe and spread east as the

Ottoman Empire came in on the side of

Like

the other missionaries during hot summer months, Harriet journeyed up into the

foothills of the

The mission property in Goezneh, as I knew it later, in 1963,

had one large building which was like a deck open to a view down the

mountain side, with kitchen behind, and a large sleeping room on each side.

I don’t know if there were more buildings in 1915, but Harriet’s

letters are mostly about tents. There

were nine people staying up there, one family with children and a number of

other teachers. They took turns

leaving at least one person on duty at the buildings in

Harriet wrote many

letters during the quiet days in Goezneh, then sent them down to a post office

whenever someone went to

At the end of the summer of 1915, Harriet’s letters mention a

group of the missionaries planning to leave, uncertain just when,

uncertain whether they would sail from Mersine or

Harriet

felt duty bound to stay in

In

a postcard, to young Mr. Nilson at

Hartford Seminary, dated January 16th 1916, Mrs. Christie wrote, “Our

two months vacation ends this week. I

shall be very glad to be in regular school work again….a number of students

cannot return for 2nd term. The

boys of military age are not likely to be here….How we’d like to have you

here. and someone else who

is here would love to have you here still more. Yes she is here for her

Christmas vacation and is more of a peach blossom than ever. She wears evenings

a lovely garnet red silk dress and tucks a rose in her hair.

Happiness becomes her….”

(The “someone else” of course was Harriet Fischer.)

Harriet’s

letters are filled with uncertainty.

She did not comment on any war activities.

But she constantly wondered when would she get to leave?

When would someone come to take her place?

There is a gap in the letters from June of 1916 until February of 1918,

by which time she was back in

From

a story she wrote after her retirement, I have learned a little of her journey

to

They

headed east by train, then reached a two mile long tunnel which was being dug

through the Amanus mountain range. Two

teams from

When

they reached

Eventually

Harriet reached the

RETURN

TO

At

the close of World War One the Ottoman Empire was divided among

The

puppet Ottoman government summoned Mustafa Kemal, hero of Gallipoli,

to lead the small army it was allowed, but he defiantly began to

form his own army. They set

out to reclaim the areas under allied protectorates.

This

then was the situation when Harriet and Paul returned to

January 22nd, 1920 the elderly Christies left

Harriet kept a baby book of the development of their little girl, Faith

Elizabeth. The last sentences in

this booklet state, “…became sick Feb. 26, listless and smileless…March 18

took her to hospital (probably in

During this private grief, Paul turned to public action.

The French had introduced legalized prostitution,

and many citizens in the decaying morals of a town under siege tried to

escape reality in drink. Paul

countered by organizing a Temperance Society, and distributing a translation of

an American pamphlet on sexual hygiene.

He wrote in a report to mission headquarters:

“This

is a mess! Turkish brigands growing

in power, the French withdrawing from outstations…now only in control of the

railroad. …City Turks fleeing from French, Armenians fleeing from Turks…everybody

afraid of everybody else.” (Stone,

p. 222 )

In the summer of 1920 there was a brief cease-fire between the guerillas

and the French. Paul and Harriet

sought some relief from the oppressive heat by riding

out to the vineyard. As they

started back, Turkish chetis appeared

and led them on their horses to

the foothills of the

The French commandant in

The Nilsons were only held captive for three days.

But immediately after they were kidnapped, telegrams had been

sent to mission headquarters in

Upon being released from their brief captivity, Paul and Harriet

were busy with relief work. The

French had cut off supplies from reaching

With the collapse of the Ottoman government and the withdrawal of

occupying allied forces, a new

Turkish state was declared on October 29th, 1923.

The Congregational mission debated the question, should they close the

schools? The young leaders of the

new republic didn’t quite know what to do about the foreign schools.

They had strong nationalistic pride, but were drawn to the quality of

education offered in the American schools. One

thing was sure, they did not want religion, even their own Islamic faith, taught

in the schools. Back in

“Abandon

Meanwhile Harriet had three more pregnancies. Those three babies also

died. (One up in Namrun)

When she became pregnant again, the

doctors insisted that she return to

May

Emily was born on May 16th of 1925.

The family lived in student housing at the

Paul Herman was born on January 28th of 1927.

When he was old enough to travel Harriet returned to

The

new government of

TALAS,

A NEW VENTURE

There had once been a medical mission and both a boys’ school and a girls’ school in Talas. These had been closed for several years. In 1927 while the Nilsons were waiting for permission to reopen the schools, they were active in general mission work, which centered in a reading room in what had once been a Protestant church. My father was busy overseeing the repairs and renovating the property in Talas. Throughout his missionary career he benefited from his experience in construction – which he had learned from his father. He also visited other villages around with his stereoptican slide machine.

He describes one such slide show to a neighboring town in February 1927:

Up on the slopes of

Besides the church is an American building.

Miss Gerber built a substantial school building

and cared for many an orphans. Her

picture looks down on the Turkish boys who are now studying in those halls to be

teachers in Turkish village schools.

My father writes of one slide show where the wives of the faculty

attended unveiled and mingled with the men.

At that time in remote villages only the most modern women appeared

unveiled. He showed pictures of

George Washington and Benjamin Franklin.

During the time of waiting for government permission to reopen Talas, my

father also taught English in the Turkish high school in

After

five years of negotiations by leading spokespersons of the Congregational

mission in

DESCRIPTION

OF TALAS in the 1930’s

After she retired, Mother wrote quite a long description of Talas so I

will base this section on her article. I

know from the dates on letters, that Harriet’s mother,

Julia Blanchard Fischer and sister Ethelwyn visited Talas once before

1929. Quite likely they traveled

back to

Talas is a

small town about five miles from the city of

While

This

snow topped

As

I remember it in the 1930s and ‘40s, the approach to Talas and most of its

business and government buildings are on

flat land, but the road rises to higher ground quite rapidly.

To reach the American school every vehicle has to follow the sweeping

road which climbs another thousand feet around the village, forming a

giant ‘S’ curve. A passenger who

does not want to ride with the luggage another two miles around

can get out and walk up 130 steps carved out of a rock precipice.

(Mother writes that at

three years old, I climbed those steps, one step at a time, plod, plod,

plod. It made Mother impatient to

keep to my pace until she realized that she could climb all the way without

stopping to rest. Those who dashed

up had to rest along the way.)

On

each side of the steps there were terraced vineyards

belonging to neighbors. The

school building was at the top, a four story stone box-like building, with a

smaller box on the side for the Nilson living quarters.

There was a large playing area for the school boys, with a sunken

volleyball court. The school also

had its own vineyards, apricot orchard, almond and walnut trees, all of which

helped to reduce the grocery bill. There

was a foot and a half thick wall whose flat surface was used for drying up to

ten bushels of apricots. These were

stewed for deserts in the winter, as well as eaten fresh during the summer.

Mother writes that the wall also served as a track for us children to run

along, and she often had to look the other way and try not to think of the sharp

drop on the other side of the wall.

Water

from the mountain streams filled caves for the school water supply, and also

filled two irrigation ponds where we children learned to swim. Drinking water

was boiled. Beyond the

vineyard and the irrigation pool there was a grassy shaded area surrounded by

lilac bushes and a honeysuckle covered wall, where the children of the previous

principal (the Wingates) were buried. Mother

liked to go there and sit on a bench by the three small graves,

to get away from bustle and noise of a school full of active boys.

And I think her thoughts may have turned from the graves of the Wingate

children, to the three small graves she had left behind on the grounds of the

EARLY

YEARS AT TALAS

The first day of the opening of the boys’ school included a brief English lesson, and also an introduction to the new Turkish alphabet, in which they learned to write “Bu Amerikan Mektebi dir. Lisan, sana’at, ve ticaret orenecegiz.” (We will learn language, trades and business). Because the alphabet had been changed American teachers had to teach the boys to read and write their own language. A Turkish teacher gave an oral geography and history lesson. Textbooks in the new alphabets were not yet available.

My father continued his story of the first day by telling of the visit of

a teacher and forty students from the Zincidere teacher training school to offer

congratulations on the reopening of the Talas school.

They had walked all the way , about four miles.

(Information about this first day comes from

Stone, pp 277, 278).

The government made a great

effort to teach people the new alphabet, and also to make sure that the remote

villages had a chance at an education. Students

who attended the government teacher training schools got a free education in

return for promising to teach a certain length of time in a village school.

The Talas Amerikan Koleji was a private boarding school offering

“language, trades and business.” Tuition

was paid by the families with some scholarship funds.

The basic course was four years including English and French, math,

science and Turkish history, and some business classes. In addition the Turkish

government helped to finance a number of poor village students who attended a

two year trade course with less emphasis on learning English.

My father was passionate about the need for these young Turks to learn a

useful trade. The poor village

students were closest to his heart.

Boarding students were required to provide some of their nonperishable

food supplies, so when the father brought the boy to school, he often led

a camel with a load of bulgur, rice, and other staples.

I remember that these trade students made skis for the winter.

But more important, these students were able to get jobs, often in the

airplane factory in

Among the first group of students was a boy named Hasan from a nearby

village. He could not afford to come

as a boarder, so lived with an uncle in Talas and walked home to his village on

weekends. He had a serious hearing

impairment which caused the other

students to torment him and call him ‘Deaf Hasan.’

In frustration he would lash back so was frequently in trouble.

Finally my father told the assembled students the story of Helen Keller,

and said “Perhaps some day Hasan will outstrip you.”

When the teasing stopped Hasan applied himself to his studies (English,

Turkish, book keeping, math, shopwork and the required Turkish subjects).

By the end of the year he was second in his class, and began to mix with

the other students, to the extent that they urged that he be accepted as a

boarder with them. So my father

appealed for scholarship money from his many contacts in

In the early 1930s depression in

Many

of the schools in eastern Anatolia had closed during World War I and the Turkish

War for

Bill

Nute had been a teacher with my

father in

Another

important person was Emily Block, ‘Aunt Emily.’ She came to

I

have just read a number of letters from Ibrahim Ertash, the school secretary

around 1946. I remember this quiet,

pleasant man in the office, but did not know his story until reading these

letters and some of my father’s. He

was one of the early students in the school, an orphan from Zincedere.

After graduation he worked eleven years in the

airplane factory in

In

the early 1930s Mother was busy with us children.

She was the station treasurer and also taught mathematics in the school.

She wrote some translations,

some from English to Turkish, and also some Turkish authors into English, such

as Gonulsuz Olmaz, by

Ahmet Agaoglu .

My

father still went to the villages

around to show pictures, only now they were black and white movies instead of

the old still pictures. We sometimes

went with him. I remember a health

movie about tuberculosis, a film about Toscanini, and some cartoons of Felix the

cat. He had the ability to

make friends with street urchins, villagers, and high government officials.

By

1941 The Turkish education system had developed its own trade schools and no

longer needed the trade school program in Talas.

What they wanted from the mission school was education that would prepare

Turkish youth for positions in the professions.

The school was to have one

year preparatory English classes, then three years junior high level school,

preparing the students to continue in the Tarsus American high school, or

The years of World War II were difficult years for the

school. My parents’ vacation year

should have come in 1941, but there were no teachers to take their place.

In June 1943, Mother brought the four of us to

My father’s vacation year was long overdue.

He left Mother in charge of

the school for the 1945/46 school year.

While at sea on the journey to

In 1952 my parents were

assigned to